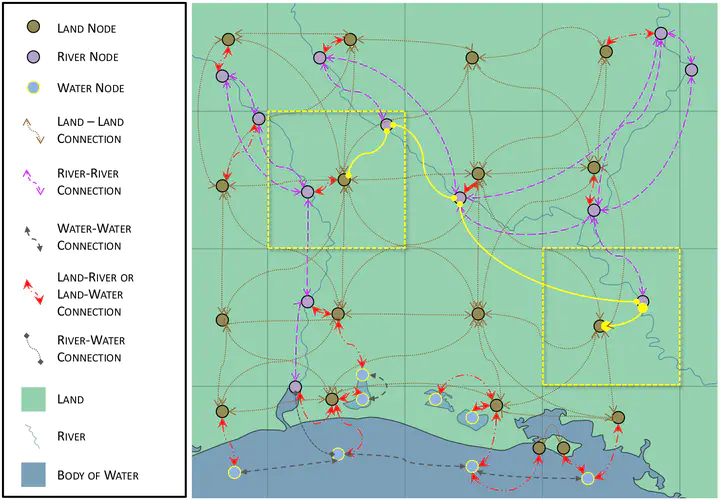

Sylized computable natural transport network

Sylized computable natural transport network

Abstract

How important are falling transport costs for patterns of population and income growth since 1000 CE? To answer this question, I build a quantitative dynamic spatial model with an agricultural and a non-agricultural sector, and endogenous fertility, migration, innovation and technology diffusion. In this model there exists an endogenous threshold for global transport costs, which is characterized by a simple network statistic. If transport costs are above this threshold, the world converges to a Malthusian steady state. If transport costs fall below this threshold, the world economy enters a process of sustained growth in population and income per capita. Taking this model to the data, I divide the globe into 2,249 3 degree by 3 degree quadrangles. I assign each location an agricultural potential determined by exogenous climate and soil characteristics. I infer bilateral transport costs by calculating the cheapest route between each pair of locations given the natural placement of rivers, oceans and mountains. I calibrate the model so that in the year 1000 the world is in a Malthusian steady state. I then drop the cost of water and land transport exogenously in a way that is consistent with historical evidence and track the endogenous evolution of population and income until the year 2000. Qualitatively, this exercise generates slow but accelerating growth in both population and income per capita for the first 800 years, an abrupt takeoff in growth after 1800 CE with Europe in the lead, and a large increase in the dispersion of income per capita after 1800 CE. Quantitatively, the model accounts for 55% of the variation in population density across 10 major regions in 1000 CE, 44% of the variation in income per capita across regions in 1800 CE, and is able to generate 43% of the overall dispersion in income per capita in 2000 CE.